#wikimedia endowment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

https://twitter.com/Plinz/status/1605310467701776384

https://nypost.com/2021/07/16/wikipedia-co-founder-says-site-is-now-propaganda-for-left-leaning-establishment/

#wikipedia#twitter#new york post#ny post#larry sanger#wikimedia#wikimedia foundation#propaganda#censorship#fake news#fundraising#charity#philanthropy#george soros#google#facebook#amazon#lobbying#wikimedia endowment

405 notes

·

View notes

Text

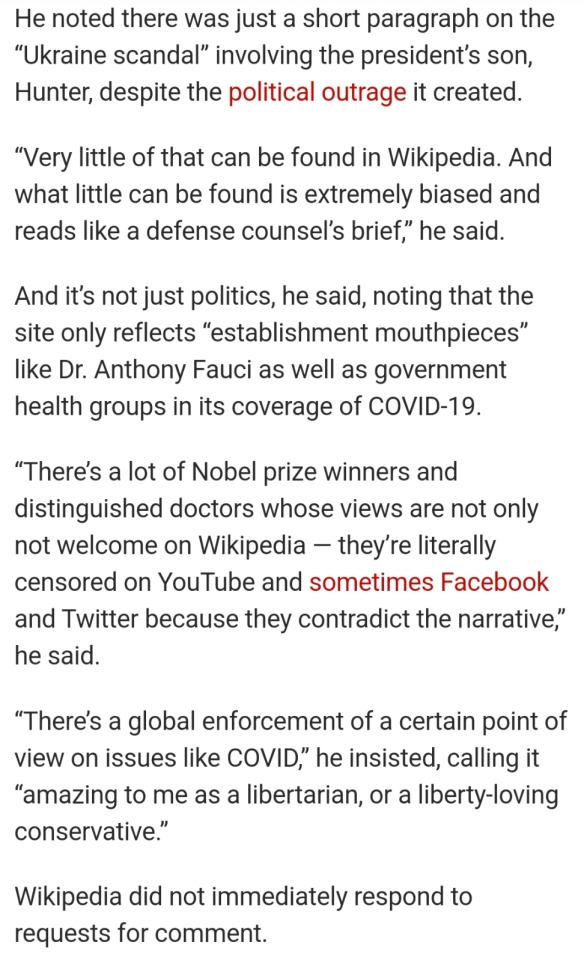

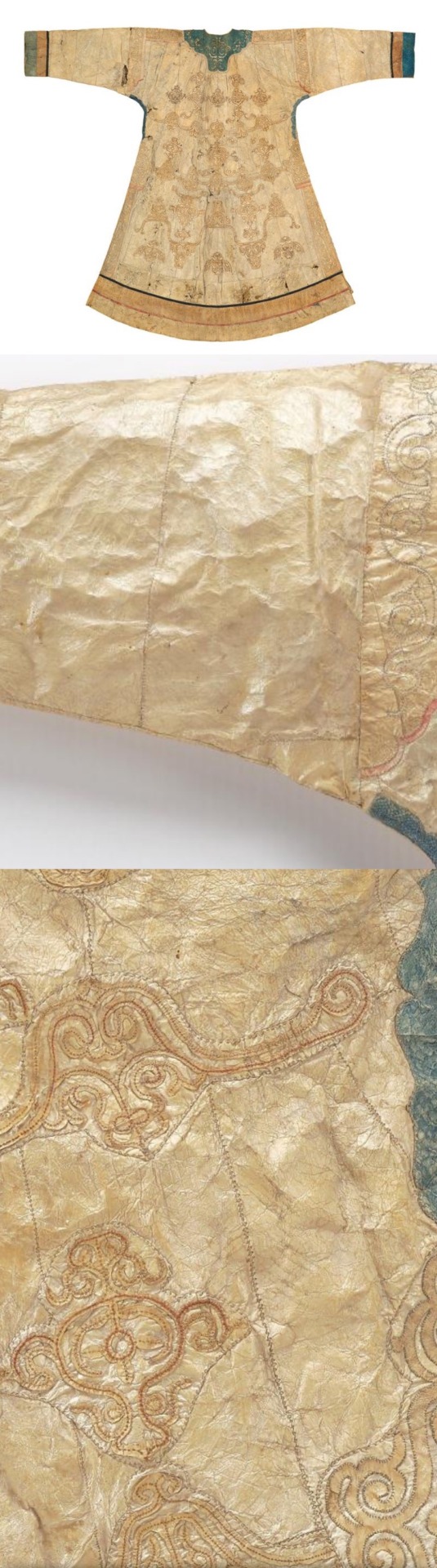

Fishskin Robes of the Ethnic Tungusic People of China and Russia

Oroch woman’s festive robe made of fish skin, leather, and decorative fur trimmings [image source].

Nivkh woman’s fish-skin festival coats (hukht), late 19th century. Cloth: fish skin, sinew (reindeer), cotton thread; appliqué and embroidery. Promised gift of Thomas Murray L2019.66.2, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, United States [image source].

Back view of a Nivkh woman’s robe [image source].

Front view of a Nivkh woman’s robe [image source].

Women’s clothing, collected from a Nivkh community in 1871, now in the National Museum of Denmark. Photo by Roberto Fortuna, courtesy Wikimedia Commons [image source].

The Hezhe people 赫哲族 (also known as Nanai 那乃) are one of the smallest recognized minority groups in China composed of around five thousand members. Most live in the Amur Basin, more specifically, around the Heilong 黑龙, Songhua 松花, and Wusuli 乌苏里 rivers. Their wet environment and diet, composed of almost exclusively fish, led them to develop impermeable clothing made out of fish skin. Since they are part of the Tungusic family, their clothing bears resemblance to that of other Tungusic people, including the Jurchen and Manchu.

They were nearly wiped out during the Imperial Japanese invasion of China but, slowly, their numbers have begun to recover. Due to mixing with other ethnic groups who introduced the Hezhen to cloth, the tradition of fish skin clothing is endangered but there are attempts of preserving this heritage.

Hezhen woman stitching together fish skins [image source].

Top to bottom left: You Wenfeng, 68, an ethnic Hezhen woman, poses with her fishskin clothes at her studio in Tongjiang, Heilongjiang province, China December 31, 2019. Picture taken December 31, 2019 by Aly Song for Reuters [image source].

Hezhen Fish skin craft workshop with Mrs. You Wen Fen in Tongjian, China. © Elisa Palomino and Joseph Boon [image source].

Hezhen woman showcasing her fishskin outfit [image source].

Hezhen fish skin jacket and pants, Hielongiang, China, mid 20th century. In the latter part of the 20th century only one or two families could still produce clothing like this made of joined pieces of fish skin, which makes even the later pieces extremely rare [image source].

Detail view of the stitching and material of a Hezhen fishskin jacket in the shape of a 大襟衣 dajinyi or dajin, contemporary. Ethnic Costume Museum of Beijing, China [image source].

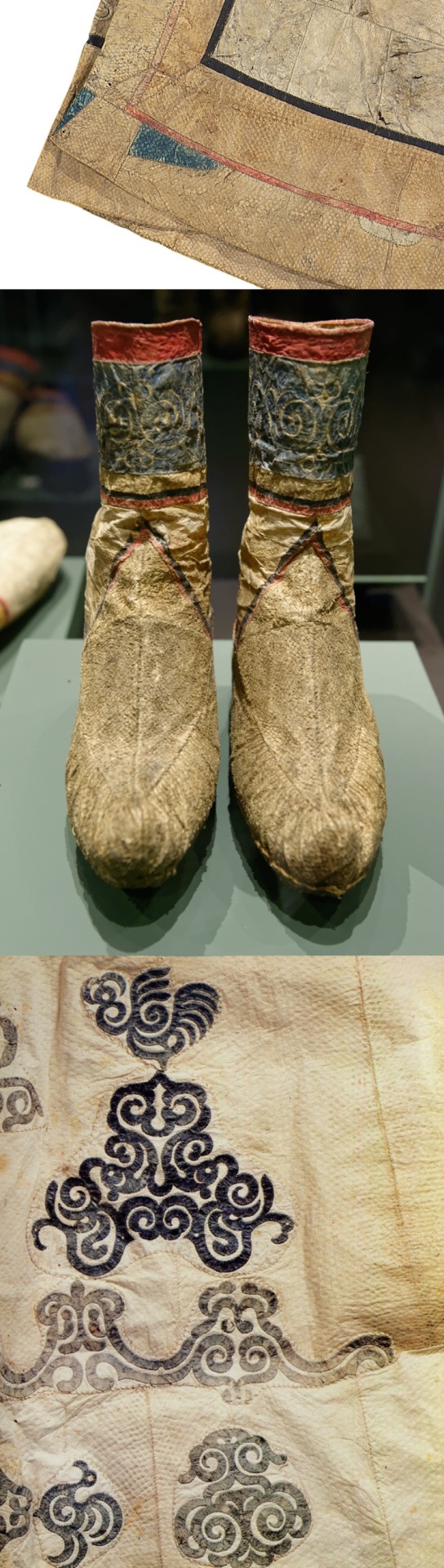

Hezhen fishskin boots, contemporary. Ethnic Costume Museum of Beijing, China [image source].

Although Hezhen clothing is characterized by its practicality and ease of movement, it does not mean it’s devoid of complexity. Below are two examples of ornate female Hezhen fishskin robes. Although they may look like leather or cloth at first sight, they’re fully made of different fish skins stitched together. It shows an impressive technical command of the medium.

赫哲族鱼皮长袍 [Hezhen fishskin robe]. Taken July 13, 2017. © Huanokinhejo / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0 [image source].

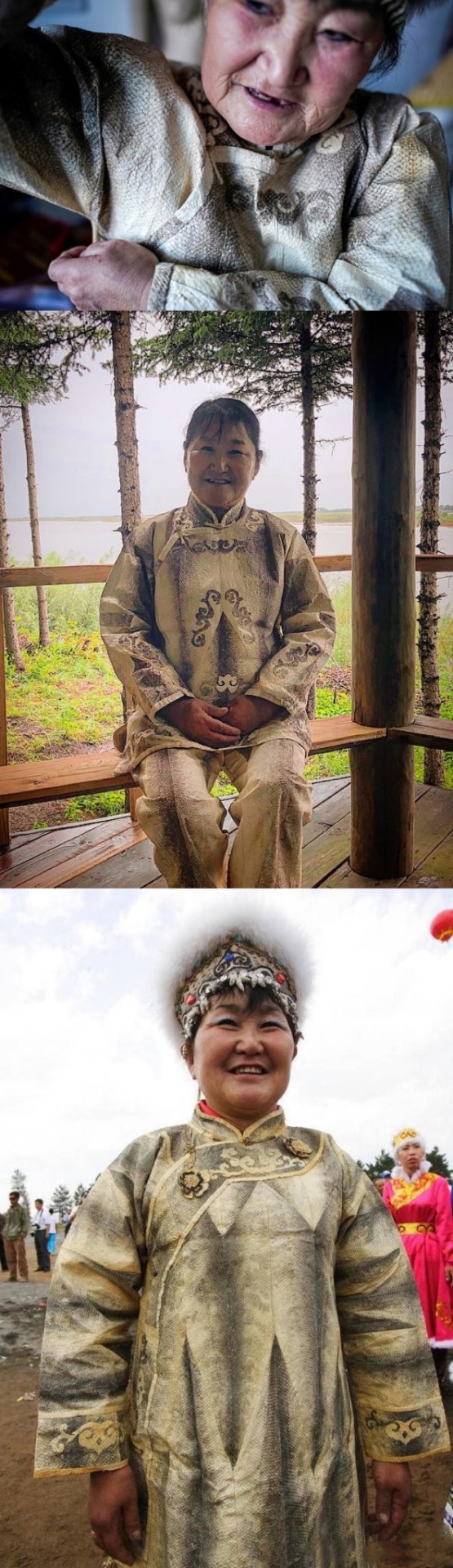

Image containing a set of Hezhen clothes including a woman’s fishskin robe [image source].

The Nivkh people of China and Russia also make clothing out of fish skin. Like the Hezhen, they also live in the Amur Basin but they are more concentrated on and nearby to Sakhalin Island in East Siberia.

Top to bottom left: Woman’s fish-skin festival coat (hukht) with detail views. Unknown Nivkh makers, late 19th century. Cloth: fish skin, sinew (reindeer), cotton thread; appliqué and embroidery. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the Mary Griggs Burke Endowment Fund; purchase from the Thomas Murray Collection 2019.20.31 [image source].

Top to bottom right: detail view of the lower hem of the robe to the left after cleaning [image source].

Nivkh or Nanai fish skin boots from the collection of Musée du quai Branly -Jacques Chirac. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0 [image source].

Detail view of the patterns at the back of a Hezhen robe [image source].

Read more:

#china#russia#tungusic#hezhe#nanai#fishskin#ethnic minorities#nivkh#chinese culture#history#russian culture#amur basin#heilongjiang#east siberia#ethnic clothing

995 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Image of President Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, center-left, with his head tilted downward. Work is in the U.S. public domain, obtained here from Wikimedia Commons.]

+

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

November 19, 2024 (Tuesday)

Heather Cox Richardson

Nov 19, 2024

For three hot days, from July 1 to July 3, 1863, more than 150,000 soldiers from the armies of the United States of America and the Confederate States of America slashed at each other in the hills and through the fields around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

When the battered armies limped out of town after the brutal battle, they left scattered behind them more than seven thousand corpses in a town with fewer than 2,500 inhabitants. With the heat of a summer sun beating down, the townspeople had to get the dead soldiers into the ground as quickly as they possibly could, marking the hasty graves with nothing more than pencil on wooden boards.

A local lawyer, David Wills, who had huddled in his cellar with his family and their neighbors during the battle, called for the creation of a national cemetery in the town, where the bodies of the United States soldiers who had died in the battle could be interred with dignity. Officials agreed, and Wills and an organizing committee planned an elaborate dedication ceremony to be held a few weeks after workers began moving remains into the new national cemetery.

They invited state governors, members of Congress, and cabinet members to attend. To deliver the keynote address, they asked prominent orator Edward Everett, who wanted to do such extensive research into the battle that they had to move the ceremony to November 19, a later date than they had first contemplated.

And, almost as an afterthought, they asked President Abraham Lincoln to make a few appropriate remarks. While they probably thought he would not attend, or that if he came he would simply mouth a few platitudes and sit down, President Lincoln had something different in mind.

On November 19, 1863, about fifteen thousand people gathered in Gettysburg for the dedication ceremony. A program of music and prayers preceded Everett’s two-hour oration. Then, after another hymn, Lincoln stood up to speak. Packed in the midst of a sea of frock coats, he began. In his high-pitched voice, speaking slowly, he delivered a two-minute speech that redefined the nation.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” Lincoln began. While the southern enslavers who were making war on the United States had stood firm on the Constitution’s protection of property—including their enslaved Black neighbors—Lincoln dated the nation from the Declaration of Independence.

The men who wrote the Declaration considered the “truths” they listed to be “self-evident”: “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” But Lincoln had no such confidence. By his time, the idea that all men were created equal was a “proposition,” and Americans of his day were “engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.”

Standing near where so many men had died four months before, Lincoln honored “those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.”

He noted that those “brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated” the ground “far above our poor power to add or detract.”

“It is for us the living,” Lincoln said, “to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.” He urged the men and women in the audience to “take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion” and to vow that “these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

[Image of President Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, center-left, with his head tilted downward. Work is in the U.S. public domain, obtained here from Wikimedia Commons.]

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#heather cox richardson#letters from an american#abraham lincoln#gettysburg#Gettysburg Address#history#American history

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Running a Thousand Miles to Freedom or, The Escape of William and Ellen ...

Preface: HAVING heard while in Slavery that "God made of one blood all nations of men," and also that the American Declaration of Independence says, that "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these, are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;" we could not understand by what right we were held as "chattels." Therefore, we felt perfectly justified in undertaking the dangerous and exciting task of "running a thousand miles" in order to obtain those rights which are so vividly set forth in the Declaration.

I beg those who would know the particulars of our journey, to peruse these pages.

This book is not intended as a full history of the life of my wife, nor of myself; but merely as an account of our escape; together with other matter which I hope may be the means of creating in some minds a deeper abhorrence of the sinful and abominable practice of enslaving and brutifying our fellow-creatures.

-W. CRAFT. 12, CAMBRIDGE ROAD, HAMMERSMITH, LONDON.

(Without stopping to write a long apology for offering this little volume to the public, I shall commence at once to pursue my simple story.)

Image is from:File:Ellen and William Craft (72a234fc-4e0a-4e3a-95f9-71aa2401000b).jpg - Wikimedia Commons

Image is from:File:Ellen Craft escaped slave.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

If you would like to read the full book, you can find many versions in your library or online. This book is in the public domain. You can find it on many sites. Ex. Project Gutenberg and Google Play Books. Disclaimer: The book is available in the public domain and may contain some historical inaccuracy. I summarize the book to the best of my ability or highlight excerpts of interesting facts. If you would like to add information, advise a current article/book, and/or critically analyze the book, it is welcome. Thank you.

#youtube#RunningAThousandMilesToFreedom#1860#TheEscapeOfWilliamAndEllenCraftFromSlavery#EllenAndWilliamCraft#EllenCraft#WilliamCraft#BlackAmerican#AfricanAmerican#BlackHistory#history#book#OldBook#HistoryInEverything

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok so I learned recently that the Wikimedia Foundation (the organization that runs Wikipedia) has a HUNDRED MILLION DOLLAR ENDOWMENT. Sure, running Wikipedia costs 10 million a year but the endowment means they can invest that money and run Wikipedia off the profits. Now, Wikipedia is still a cool site doing cool work, and if you are able and you like supporting good causes you should definitely donate! But their fundraising banners are kinda misleading.

hey i know a lot of you cannot donate, but wikipedia NEEDS money to keep functioning. AO3 was able to surpass their fundraising goal in days, but wikipedia has been trying to get donations for months now to no avail. that’s not a “don’t donate to AO3”, that’s a “also donate to wikipedia” or “donate to wikipedia instead, because AO3 is doing good”. if any of you can donate, please do. wikipedia is one of the best things to happen on the internet, and i would hate to see it with tons of ads or worse.

donate to wikipedia!!

24K notes

·

View notes

Link

#arturo_sandoval_arocha#Jazz#JazzReview#lindamayhanoh#NewYorkJazz#NewYorkNightLife#ny_jazzmasters#Openingnight.Reviews#patmetheny

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Wikimedia Foundation is financially healthy and nearing a $100M endowment target five years ahead of schedule, yet fundraising appeals imply it's struggling (Andreas Kolbe/The Daily Dot)

The Wikimedia Foundation is financially healthy and nearing a $100M endowment target five years ahead of schedule, yet fundraising appeals imply it's struggling (Andreas Kolbe/The Daily Dot)

Andreas Kolbe / The Daily Dot: The Wikimedia Foundation is financially healthy and nearing a $100M endowment target five years ahead of schedule, yet fundraising appeals imply it’s struggling — The site is way richer than it wants you to know. — The Wikimedia Foundation (WMF), the non-profit that owns Wikipedia … Source link

View On WordPress

#100M#ahead#Andreas#appeals#daily#Dot#endowment#financially#Foundation#fundraising#healthy#imply#it039s#KolbeThe#nearing#schedule#struggling#target#Wikimedia#years

0 notes

Text

Talking Together: The Earliest Record of A Scottish Parliament?

(A ninteenth century engraving of the great seal of Alexander II. Source- Wikimedia Commons)

On 8th April 1236, letters were issued on behalf of King Alexander II of Scotland, recording the settlement of a recent dispute between the Cistercian monks of Melrose and the nobleman Roger Avenel. Although at first sight this may appear unremarkable, the document which contains the Crown’s record of this settlement can be considered the earliest official evidence of a Scottish parliament.

Some time before 1236, Roger Avenel and his ancestors had granted use of some land in Eskdale (Dumfriesshire) to Melrose Abbey. The Abbey was heavily involved in wool and leather production. Access to upland grazing for the abbey’s livestock, as well as timber and arable, would have made this Eskdale land extremely valuable to the monks. Unfortunately for them, Roger Avenel also felt entitled to use the land exactly as he pleased, and had no qualms about obstructing the same monks he and his predecessors had endowed. Despite the terms of his previous charter, Roger and his men loosed their horses and other animals on the land, and destroyed the houses, ditches, and enclosures made by the Abbey. In order to settle “the controversies stirred between them on this account”, the dispute between the two parties was brought before the highest judge in the realm- King Alexander II of Scotland. Eventually, a compromise was reached, providing for the use of the land by both Melrose Abbey and Roger Avenel, albeit in different ways. The warring parties were thus reconciled, “in the presence of our barons at the colloquium at Liston”, in the year of grace 1235.

It is likely that the letters which record this settlement were made at least a couple of weeks after this assembly at Kirkliston, since they are dated 8th April “in the twenty-second year of the reign of our lord the king”- i.e. 1236.* The document itself was witnessed by Andrew, bishop of Moray; Clement, bishop of Dunblane; Walter Comyn, the earl of Menteith; Walter, the Steward of Scotland; Walter Oliphant, justiciar of Lothian; Henry Balliol; David Keith, the Marischal; and Geoffrey, the clerk of the liverance. This cannot be taken as a list of everyone who attended the ‘colloquium’ at Kirkliston, though I would argue that most of these men were probably present anyway. Nonetheless the letter is possibly the earliest surviving “official” Crown record of what we now call the Scottish parliament- though this is by no means certain since the early history of this institution is shadowy and fraught with ambiguity...

(The old kirk of Liston, presumably near to where the ‘colloquium’ of 1235 took place. The church has its roots in the Middle Ages and may have been standing at the time of the first Scottish parliament. Source is picture by Tom Sargent who has kindly made this picture available on wikimedia commons for reuse under the Creative Commons License)

The early development of “parliament” in Scotland is even more obscure than in neighbouring England. Very few Crown documents have survived from the thirteenth century which relate to meetings that could be considered parliaments, and even the terminology used to describe the kinds of assembly we now call parliament can be ambiguous. Thirteenth century writers do not always use the same terminology we would expect, and it is unclear whether the words they actually use had exactly the same meaning in the thirteenth century as they do now, and indeed whether these words were used consistently. Some mediaeval chroniclers do refer to certain assemblies which were held by the kings of Scotland before 1235, and which they give the name “parliament”. In one Anglo-Norman work, the twelfth century chronicler Jordan Fantosme states that William the Lion held “sun plenier parlement” (translated as his “plenary” or “full” parliament) in 1173, when he wanted to consult the wise men of his kingdom on whether or not he should support the rebellion of Henry “the Young King” against the latter’s father Henry II of England. “Gesta Annalia”, a late thirteenth century Scottish chronicle, also uses a Latinised version of the French term “parliament”, to describe an assembly held by King Alexander II in 1215. However, no official documents associated with these “parliaments” survive, and the chroniclers who referred to them did not define their use of the term.

In records produced on behalf of the Scottish Crown, the word “parliament” itself doesn’t appear very often before the end of the thirteenth century. However quite a few surviving records do use the Latin word “colloquium” to refer to certain assemblies of the king and his barons- indeed this is the word used to describe the meeting held at Kirkliston in 1235. “Colloquium” has a similar meaning to the French word “parliament”, in that they both loosely describe a “talking together” or a discussion. In thirteenth century England, the Latin and French terms were often treated as interchangeable, and so early twentieth century historians, searching for early evidence of a similar institution in Scotland, were quick to identify any colloquium mentioned in Scottish records as a parliament in the usual sense of the word. However the word also carries its fair share of ambiguity. We do not know whether a “colloquium” in thirteenth century Scotland would have looked anything like our idea of a mediaeval parliament, nor whether the term always meant the same thing, nor can we identify what it was that set a “colloquium” apart from any other assembly or council in which the king of Scots consulted his leading vassals. There is also the danger that, having first encountered the terms “colloquium” and parliament in English and French contexts, historians have gone looking for a similar phrase in Scottish sources and inadvertently analysed the evidence through a subjective lens, based on a preconceived notion of what a parliament was.

Although more recent historians have acknowledged this danger, unfortunately the nature of the surviving evidence seems to compel them to work within the same framework, using the existed, if limited, terminology as best they can. The “colloquium” of thirteenth century Scotland does seem to be the closest thing we have to a word for the kind of formal assembly of the political community, chaired by a king, which we might describe more easily as a parliament in late mediaeval and early modern Scotland. It is also possible (indeed, likely) that the colloquium held at Kirkliston in 1235 was not the first of its kind. Nonetheless with such fragmentary evidence, it is probably reasonable to view that assembly as a very distant ancestor of the Scottish parliament that we know today.

So what might this parliament have looked like? During the Late Middle Ages, yet another phrase was commonly used to refer to both parliaments and general councils in Scotland- these were described as meetings of the “Three Estates”. This seems to have originated from the mediaeval theory that a Christian society should be made up of three sorts of people: those who prayed, those who fought, and those who worked. Different parts of Christian Europe developed regional variations on this theory but, in the context of the Scottish parliament, the “First Estate” (those who prayed) tended to refer to the higher clergy (bishops and important abbots). The “Second Estate” (those who fought) meant the higher nobility (from dukes down to lords of parliament and richer freeholders), and the “Third Estate” (those who worked) only referred to the commissioners elected to represent the country’s burghs (so not the common man as such).

However, in 1235 this parliamentary model had not yet evolved. The exact composition of thirteenth century Scottish parliaments is obscure, but in the record of the colloquium held at Kirkliston only the king and his ‘barons’ are mentioned. Evidence from other thirteenth century assemblies indicates that it was primarily members of the higher nobility who attended these- earls and the most powerful barons. Although they are not mentioned in the record of the Kirkliston assembly, the kingdom’s bishops also seem to have been permitted to attend these other “parliaments”. Burgh representatives do not appear until the 1290s, and A.A.M. Duncan has argued that they were not a regular fixture until much later. The other freeholders of Scotland (below the rank of earl and great baron) also do not seem to have attended parliament much before the fourteenth century. So the colloquium at Kirkliston in 1235 was probably just a meeting of the king and his leading nobles, though perhaps some of the bishops also attended.

In any case, the number of attendees would probably have been quite small- G.W.S. Barrow has argued that they would have “numbered in dozens or scores rather than in hundreds”. Also the Scottish parliament was always unicameral, in contrast to the English institution, which seems to have developed its separate Houses by at least the mid-fourteenth century. There was also no fixed location where parliaments were held as yet, and aside from the 1235 assembly at Kirkliston, during the thirteenth century meetings were also held in Stirling, Roxburgh, Holyrood Abbey, Edinburgh, and Scone, among other places. Like the king, parliament would remain peripatetic for centuries, and though Edinburgh eventually emerged as the most popular location during the reigns of James II and James III, the Scottish parliament only established itself there permanently in the seventeenth century**. Other customs associated with pre-Union Scottish parliaments- for example the Riding of Parliament or the Lords of the Articles- were also probably unknown in the thirteenth century.

(The Scottish parliament or Estates processing in the late seventeenth century. Source- Wikimedia Commons)

Wherever they met and whoever attended, mediaeval parliaments must have differed in some way from regular assemblies. Their most basic function was to provide an opportunity for the king to consult the political community on important issues. But historians are divided over just what kind of issue which would have dominated proceedings at early parliaments. Twelfth and thirteenth century chroniclers seem to have been interested in the assembly’s role as a venue for political debate and diplomatic activity. However this was probably only part of the story. Meanwhile parliament’s financial role (approving extraordinary taxation) which was to be such an important factor in the development of the institution in England, does not appear to have been quite so central in Scotland. A third function of most parliaments- one which is particularly important in our own day- is to develop and enact laws. This was probably performed by early Scottish parliaments too, but we lack evidence for substantial legislative activity before the fourteenth century.

In 1928, while surveying the evidence of earlier thirteenth century assemblies as a preliminary to their investigation of Edward I of England’s Scottish parliaments, the historians H.G. Richardson and George Sayles focused on parliament’s function as the highest court in the land. They came to the conclusion that, “the primary purpose of these early parliaments of Scotland was the dispensing of justice.” Certainly this is the role which we can see the colloquium at Kirkliston performing in the single surviving record which that assembly produced. The next documented colloquium, which met in 1248 at Stirling, is also known only from the record of an arbitration which took place there, again under the eye of Alexander II, while legal cases again crop up on several occasions during the reigns of Alexander III and John Balliol and the minority of Margaret (the remainder of the documented parliamentary business during the late thirteenth century is largely concerned with international diplomacy, which may however simply be due to the fact that this was the only subject which was considered important enough to record). However, in the 1960s, A.A.M. Duncan disagreed with Richardson and Sayles’ verdict, pointing out that the fragmentary nature of the evidence makes it difficult to assign special significance to any one function of the early parliaments. For his own part, Duncan characterised the early Scottish parliament as a venue for the promotion of the Crown’s interests, and “the occasion on which the rights of the king could be asserted by customary judicial process with final authority.”

(The coat of arms of Alexander II of Scotland, as portrayed in the thirteenth century ‘Historia Anglorum’ of Matthew Paris. Reproduced by permission of the British Library under a Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.)

Given that any debate which can be had about the early Scottish parliament’s early activities is severely limited by the patchy and ambiguous evidence available, it is perhaps unsurprising that some historians have tended to dismiss the colloquium of 1235 and other early assemblies as hurriedly as possible, moving onto the better documented meetings after 1286. As discussed above, sometimes this has even led to doubt over whether the 1235 meeting can fairly be called the earliest parliament at all. As Keith M. Brown, Alastair J. Mann, and Roland J. Tanner state in their historical introduction to the online “Records of the Parliament of Scotland” project:

“Between 1235 and 1286, therefore, parliament exists for historians in a kind of limbo – we can see that the term is used (in the early colloquium form), but can tell almost nothing about what was meant by that term. What set the early colloquia apart from previous assemblies of the king and his subjects has been lost, although there could have been a clear distinction, and the primary purpose of those early assemblies is unknown – whether they were political, judicial or legislative. There are no criteria that can be used for parliament’s emergence other than the moment that contemporary Scots began to refer to their assemblies in official sources by either the word parliamentum or colloquium. The debate about the earliest known Scottish parliament, therefore, becomes very simple – it was the Kirkliston colloquium held in 1235. Whether this was the first assembly to be referred to as such, or whether it differed in any significant way from the royal councils and assemblies that had occurred before will almost certainly never be known.”

If there is anything else to be said, it is only that, over the centuries which followed the Kirkliston meeting, the Scottish parliament evolved in many different ways, most of which could not have been foreseen by any of the men present in 1235. The mediaeval institution did at different points in its history perform a variety of functions, whether political, financial, legislative, or judicial, and although the Crown did often attempt to use parliament to bolster its own position, communication between the two was not a one-way street, and on several occasions the Estates talked back. In the early modern period, further development of the institutions and ceremonial associated with parliament occurred, while the abolition of the institution in 1707 followed a century which had seen parliament operating in new territory on more than one occasion. The current devolved parliament, which met for the first time in nearly three centuries in 1999 and usually sits at Holyrood*** is not only a very different body to that which met at Kirkliston over six hundred years earlier, but has itself changed since it was reconvened over twenty years ago. Nonetheless, a line can be drawn between the shadowy, probably elitist, assembly which took place in 1235 and the principle of public consultation which is supposed to underly Scottish democracy today. Though political systems and values must inevitably evolve over time, and though many historical events are obscure, difficult to define, and not easily subsumed into a greater narrative, the colloquium at Kirkliston is at least worth remembering as the first stage in, “the journey begun long ago and which has no end.”

(The debating chamber in the current Scottish parliament building. Source- wikimedia commons, where this photo was kindly shared by user:pschemp)

Additional Notes:

*In many official and religious documents from the Middle Ages, the year was reckoned to begin on 25th March. So if the colloquium took place in 1235 but the letters were not made until 8th April 1236, then at least a fortnight must have passed between the date when the settlement between Melrose and Roger Avenel actually took place and the date when a document was created to record this.

** Interestingly Holyrood, where the modern parliament is now based, was technically in a separate burgh from Edinburgh in the Middle Ages, the burgh of Canongate.

***When it is not in recess, which it is currently in the run-up to the May elections.

Selected Bibliography:

- Records of the Parliaments of Scotland website and in particular the record of the Kirkliston Colloquium listed under the reign of Alexander II and the historical introduction. This website is a magnificent resource, so I encourage people to look it up anyway.

- Jordan Fantosme’s “Chronicle of the War Between the English and the Scots”, translated by Francisque Michel.

- “The Early Parliaments of Scotland”, by A.A.M. Duncan as published in the Scottish Historical Review, vol. 45 no. 139 Part 1 (April 1966). Link is to JSTOR.

- “The Scottish Parliaments of Edward I”, by H.G. Richardson and George Sayles, as published in the Scottish Historical Review, vol. 25, no. 100 (Jul. 1928). Link is to JSTOR.

- “The Origins and Development of the Scottish Parliament, 1249-1329″, by Alison A.B. MacQueen. Thesis submitted for award of PhD, available on St Andrews research repository here

- “1999 Speech at Opening of the Scottish Parliament”, given by Donald Dewar

#Ugh not my best writing and I will probably slim it down and tidy it up over the weekend but I want to at least try to publish on the 8th#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#Scottish parliament#Thirteenth century#1230s#Kirkliston#West Lothian#Edinburgh#Holyrood#parliament#constitutional history#democracy#power and politics#government#political history#Alexander II#Roger Avenel#Melrose Abbey#Cistercians#The Three Estates#Clement bishop of Dunblane#Walter Comyn Earl of Menteith#Walter Fitzalan/Stewart 3rd Steward of Scotland

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm certainly not going to tell you that you shouldn't donate to Wikipedia - I have! - but it's really not a "before it's too late" situation. Despite the big red banners (which Wikipedia editors have protested as misleading to the point of being unethical), Wikipedia is doing pretty all right. The Wikimedia Foundation recently finished setting up an endowment, and their latest financial audit indicated that they were in a healthy position.

Musk is being an ass, but Wikipedia doesn't actually need him, and unlike purchasing a publicly-traded company there's little danger of a well-established and secure nonprofit turning over.

If you want to help Wikipedia, they need editors more badly than they need a couple bucks. You don't have to start big, but next time you see a typo or a [citation needed] consider seeing if you can help out.

Again donate to Wikimedia if you want, that's great, but they aren't facing bankruptcy if you don't.

“…the sight of Elon Musk charging towards Wikipedia with his trademark guile and delicacy was so predictable that it was almost relaxing. He saw a collective resource that people prized and he wanted to hurt it.”

Thoth knows Wikipedia’s not perfect, but I’d sooner have it handy than not have it.

38K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Posted by Samantha Hughes-Johnson.

On this day (30 September) in 1487, Luca Landucci, the apothecary and Florentine diarist, informs us that the relics of Saint Jerome,

“were taken from the altar of the Cross at Santa Maria del Fiore and were set in silver and gold, very richly, at a great cost; and then a fine procession was made, and they were replaced in the said chapel with much reverence. This was done at the cost of the estimable Messer Jacopo Manegli, one of the canons of the said church. It was reported that he had spent 500 gold florins on the setting; and besides this he had endowed a chapel. And every year these beautiful relics were devoutly carried in procession.”

Images: Antonio di Salvi Salvucci, The Reliquary of Saint Jerome, 15th Century, gilded Silver with translucent enamel, Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

References: Luca Landucci, A Florentine Diary From 1450-1516 by Luca Landucci: contiued by an anonymous writer ‘till 1542 with notes by Iodoco del Badia. Trans. Alice de Rosen Jervis, London: J. M. Dent and Sons, 1927, pp. 43-44.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Craigslist Founder Donates $500,000 To Curb Wikipedia Trolls SAN FRANCISCO (CBS/AP) — Craigslist founder Craig Newmark is donating $500,000 to help curb harassment on Wikipedia.

0 notes

Quote

Google is pouring an additional $3.1 million into Wikipedia, bringing its total contribution to the free encyclopedia over the past decade to more than $7.5 million, the company announced at the World Economic Forum Tuesday. A little over a third of those funds will go toward sustaining current efforts at the Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit that runs Wikipedia, and the remaining $2 million will focus on long-term viability through the organization’s endowment.

Google Gives Wikimedia Millions—Plus Machine Learning Tools

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wikipedia: A Disinformation Operation?

— Published: March 2020 | Updated: January 2022 | Swiss Policy Research

Is Wikipedia an Open Encyclopedia or a Covert Disinformation Operation?

Wikipedia is generally thought of as an open, transparent, and mostly reliable online encyclopedia. Yet upon closer inspection, this turns out not to be the case.

In fact, the English Wikipedia with its 9 billion worldwide page views per month is governed by just 500 active administrators, whose real identity in many cases remains unknown.

Furthermore, studies have shown that 80% of all Wikipedia content is written by just 1% of all Wikipedia editors, which again amounts to just a few hundred mostly unknown people.

Obviously, such a non-transparent and hierarchical structure is susceptible to corruption and manipulation, the notorious “paid editors” hired by corporations being just one example.

For instance, in 2015 a German Wikipedia administrator was exposed as a project manager at pharmaceutical company Merck who whitewashed Wikipedia articles on Merck’s history and products. Yet despite the exposure, the manager remained a Wikipedia administrator.

Already in 2007, researchers found that one of the most active and influential English Wikipedia administrators, called “Slim Virgin”, was in fact a former British intelligence informer.

Also in 2007, researchers found that CIA and FBI employees were editing Wikipedia articles on controversial topics, including the Iraq war and the Guantanamo military prison.

More recently, another highly prolific Wikipedia editor going by the name of “Philip Cross” turned out to be linked to British intelligence as well as several mainstream media journalists.

In Germany, one of the most aggressive Wikipedia editors was exposed, after a two-year legal battle, as a political operative formerly serving in the Israeli army as a foreign volunteer.

In fact, the Israeli Ministry of Strategic Affairs is known to coordinate hundreds of activists who extensively edit Wikipedia and other websites to reflect Israeli interests.

Even in Switzerland, unidentified government employees were caught whitewashing Wikipedia entries about the Swiss secret service just prior to a public referendum about the agency.

Many of these Wikipedia personae are editing articles almost all day and every day, indicating that they are either highly dedicated individuals, or in fact, operated by a group of people.

In addition, articles edited by these personae cannot easily be revised, since the above-mentioned administrators can always revert changes or simply block disagreeing users altogether.

The primary goal of these covert campaigns appears to be promoting establishment and industry positions while destroying the reputation of critics. In this regard, German watchdog group Wiki-Radar described Wikipedia as “the most dangerous website on the internet”.

Articles most affected by this kind of manipulation include medical, political, and certain historical topics as well as biographies of non-compliant academics, journalists, and politicians.

One of the most important groups manipulating Wikipedia are the so-called “Skeptics”, an obscure organization that is “skeptical” of people and positions challenging official narratives. Former German intelligence chief Dr. Helmut Roewer descibed them as a “cult-like criminal organization” used as “cyber warriors” by both corporations and intelligence services to attack their critics.

Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, a friend of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and a “Young Leader” of the Davos World Economic Forum, has repeatedly defended these operations.

Speaking of Davos, Wikimedia has itself amassed a fortune of more than $160 million, donated in large part not by lazy students, but by major US corporations and influential foundations.

The current Wikimedia CEO, Katherine Maher, previously worked at the US Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) as well as at a subgroup of the US National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Moreover, US social media and video platforms are increasingly referring to Wikipedia to frame or combat “controversial” topics. The revelations discussed above may perhaps help explain why.

Already NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed how spooks manipulate online debates, and more recently, a senior Twitter executive turned out to be a British Army “psyops” officer.

To add at least some degree of transparency, German researchers have developed a free web browser tool called WikiWho that lets readers color code just who edited what in Wikipedia.

In many cases, the result looks as discomforting as one might expect.

WikiWho / WhoColor (source)

0 notes

Text

Lignum vitae - Wikipedia

To all our readers,

Please don't scroll past this. This is the 1st time we've interrupted your reading recently, so we'll get straight to the point: This Monday we need you to make a donation to the Wikimedia Endowment to protect Wikipedia's future. 98% of our readers don't give; they simply look the other way. If you are one of our rare donors, we warmly thank you.

If everyone reading this donated $2.75, we could keep Wikipedia thriving for years. The price of a cup of coffee is all we need. We're sure you are busy and we don't mean to interrupt you, but we must remind everyone.

We don’t charge a subscription fee, and Wikipedia is sustained by the donations of only 2% of our readers. Without reader contributions, big or small, we couldn’t run Wikipedia the way we do.

That’s why we still need your help. We are passionate about our model because at its core, Wikipedia belongs to you. We want to make sure everyone on the planet has equal access to knowledge.

If Wikipedia provided you $2.75 worth of knowledge this year, please take a minute to secure its future by making a gift to the Wikimedia Endowment. Thank you

0 notes

Text

Saturday: Preparation for the Twenty-third Sunday in Ordinary Time

Complementary Hebrew Scripture from the Latter Prophets: Isaiah 33:1-9

Ah, you destroyer, who yourself have not been destroyed; you treacherous one, with whom no one has dealt treacherously! When you have ceased to destroy, you will be destroyed; and when you have stopped dealing treacherously, you will be dealt with treacherously.

O Lord, be gracious to us; we wait for you. Be our arm every morning, our salvation in the time of trouble. At the sound of tumult, peoples fled; before your majesty, nations scattered. Spoil was gathered as the caterpillar gathers; as locusts leap, they leaped upon it. The Lord is exalted, he dwells on high; he filled Zion with justice and righteousness; he will be the stability of your times, abundance of salvation, wisdom, and knowledge; the fear of the Lord is Zion's treasure.

Listen! the valiant cry in the streets; the envoys of peace weep bitterly. The highways are deserted, travelers have quit the road. The treaty is broken, its oaths are despised, its obligation is disregarded. The land mourns and languishes; Lebanon is confounded and withers away; Sharon is like a desert; and Bashan and Carmel shake off their leaves.

Semi-continuous Hebrew Scripture from the Writings: Proverbs 8:1-31

Does not wisdom call, and does not understanding raise her voice? On the heights, beside the way, at the crossroads she takes her stand; beside the gates in front of the town, at the entrance of the portals she cries out: “To you, O people, I call, and my cry is to all that live. O simple ones, learn prudence; acquire intelligence, you who lack it. Hear, for I will speak noble things, and from my lips will come what is right; for my mouth will utter truth; wickedness is an abomination to my lips. All the words of my mouth are righteous; there is nothing twisted or crooked in them. They are all straight to one who understands and right to those who find knowledge. Take my instruction instead of silver, and knowledge rather than choice gold; for wisdom is better than jewels, and all that you may desire cannot compare with her. I, wisdom, live with prudence, and I attain knowledge and discretion. The fear of the Lord is hatred of evil. Pride and arrogance and the way of evil and perverted speech I hate. I have good advice and sound wisdom; I have insight, I have strength. By me kings reign, and rulers decree what is just; by me rulers rule, and nobles, all who govern rightly. I love those who love me, and those who seek me diligently find me. Riches and honor are with me, enduring wealth and prosperity. My fruit is better than gold, even fine gold, and my yield than choice silver. I walk in the way of righteousness, along the paths of justice, endowing with wealth those who love me, and filling their treasuries.”

The Lord created me at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of long ago. Ages ago I was set up, at the first, before the beginning of the earth. When there were no depths I was brought forth, when there were no springs abounding with water. Before the mountains had been shaped, before the hills, I was brought forth— when he had not yet made earth and fields, or the world’s first bits of soil. When he established the heavens, I was there, when he drew a circle on the face of the deep, when he made firm the skies above, when he established the fountains of the deep, when he assigned to the sea its limit, so that the waters might not transgress his command, when he marked out the foundations of the earth, then I was beside him, like a master worker; and I was daily his delight, rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race.

Complementary Psalm 146

Praise the Lord! Praise the Lord, O my soul! I will praise the Lord as long as I live; I will sing praises to my God all my life long.

Do not put your trust in princes, in mortals, in whom there is no help. When their breath departs, they return to the earth; on that very day their plans perish.

Happy are those whose help is the God of Jacob, whose hope is in the Lord their God, who made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them;¹ who keeps faith forever; who executes justice for the oppressed; who gives food to the hungry.

The Lord sets the prisoners free; the Lord opens the eyes of the blind. The Lord lifts up those who are bowed down; the Lord loves the righteous. The Lord watches over the strangers; he upholds the orphan and the widow, but the way of the wicked he brings to ruin.

The Lord will reign forever, your God, O Zion, for all generations. Praise the Lord!

¹This passage is found at least three times in the Christian Scriptures. In Acts 4:24 it is part of a prayer in which believers pray for boldness. The prayer is at Acts 4:23-31. Later in Acts (14:15), Paul uses the phrase in responding to the crowds in Lystra, who want to offer sacrifices to him and Barnabas. His speech is at Acts 14:8-18. Finally, in Revelation 10:6, it is part of a speech by an angel holding a small scroll. The speech is at Revelation 10:1-7.

Semi-continuous Psalm 125

Those who trust in the Lord are like Mount Zion, which cannot be moved, but abides forever. As the mountains surround Jerusalem, so the Lord surrounds his people, from this time on and forevermore. For the scepter of wickedness shall not rest on the land allotted to the righteous, so that the righteous might not stretch out their hands to do wrong. Do good, O Lord, to those who are good, and to those who are upright in their hearts. But those who turn aside to their own crooked ways the Lord will lead away with evildoers. Peace be upon Israel!

New Testament Gospel Lesson: Matthew 15:21-31¹

Jesus left that place and went away to the district of Tyre and Sidon. Just then a Canaanite woman from that region came out and started shouting, “Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David; my daughter is tormented by a demon.” But he did not answer her at all. And his disciples came and urged him, saying, “Send her away, for she keeps shouting after us.” He answered, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” But she came and knelt before him, saying, “Lord, help me.” He answered, “It is not fair to take the children's food and throw it to the dogs.” She said, “Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters' table.” Then Jesus answered her, “Woman, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.” And her daughter was healed instantly.

After Jesus had left that place, he passed along the Sea of Galilee, and he went up the mountain, where he sat down. Great crowds came to him, bringing with them the lame, the maimed, the blind, the mute, and many others. They put them at his feet, and he cured them, so that the crowd was amazed when they saw the mute speaking, the maimed whole, the lame walking, and the blind seeing. And they praised the God of Israel.

¹There is a parallel passage at Mark 7:24-30, which is the Sunday Gospel lesson this week.

Year B Ordinary 23 Saturday

Selections from Revised Common Lectionary Daily Readings, copyright © 1995 by the Consultation on Common Texts. Unless otherwise indicated, Bible text is from The New Revised Standard Version, (NRSV) copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All right reserved. Footnotes in the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) that show where the passage is used in the Christian Scriptures (New Testament) from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB) by David H. Stern, Copyright © 1998 and 2006 by David H. Stern, used by permission of Messianic Jewish Publishers, www.messianicjewish.net. All rights reserved worldwide. When text is taken from the CJB, the passage ends with (CJB) and the foregoing copyright notice applies. Parallel passages are as indicated in The Holy Bible Modern English Version (MEV), copyright © 2014 by Military Bible Association. Used by permission. All rights reserved. When text is taken from the MEV, the passage ends with (MEV) and the foregoing copyright notice applies. Image Credit: The Woman of Canaan at the Feet of Christ by Jean Germain Drouais, via Wikimedia Commons. This is a public domain image.

#B Ordinary 23 Saturday#miracles by Jesus#Canaanite woman#Galilee#Salvation#righerousness#wisdom#prudence#understanding

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m actually going to push back against this a bit, but only on the point made about Wikipedia. Wikipedia is part of a 501(c)(3) nonprofit company that has more donations than it honestly needs to cover costs of staff and servers. Without that nonprofit status, it would have a lot less credibility than it currently does as it would have to rely on things like ad revenue for funding and that comes with it’s own baggage (see: youtube and all the problems with the algorithm there). Now, the endowment is massive, over 100 mil. USD, but it seeks donations because that’s just how they handle their costs. Now, that doesn’t mean they need the money, but it costs about $10 million dollars a year approximately to operate the Wikimedia Foundation (the actual nonprofit, besides Wikipedia they also run stuff like Wikictionary and Wikimedia, among others). The endowment just ensures that the Wikimedia Foundation can continue operating. There’s still some issues with the democratization of knowledge and bias and stuff, but that’s just to be expected. Wikipedia and the other wikis the foundation operates are more good than not, and making it seem like there’s a profit motive there just feels disingenuous since they legally can’t. They don’t even have shareholders...

I think like, the death of Vine and Rabbit, Wikipedia constantly needing to beg for money, Discord depending so heavily on venture capital, Facebook turning towards spying on users to generate a return on all the venture capital that got them started, Adobe creative suite turning into a subscription rather than a single product you buy, the strangulation of streaming entertainment as every company pulls their content and makes it exclusive to their service, are all great examples of how like, it really doesn't matter if something is legitimately useful, efficient, or beloved, it is next to impossible for a service to exist if it doesn't make shareholders increasing amounts of money year after year. Which may seem like a "no duh" type of statement, but it's a very simple window into how the profit motive makes products and services worse, not better. And how that's not just a matter of certain companies or ceos being bad and greedy on an individual level, but is an inescapable factor of an economy where existence is dependent on generating capital.

119K notes

·

View notes